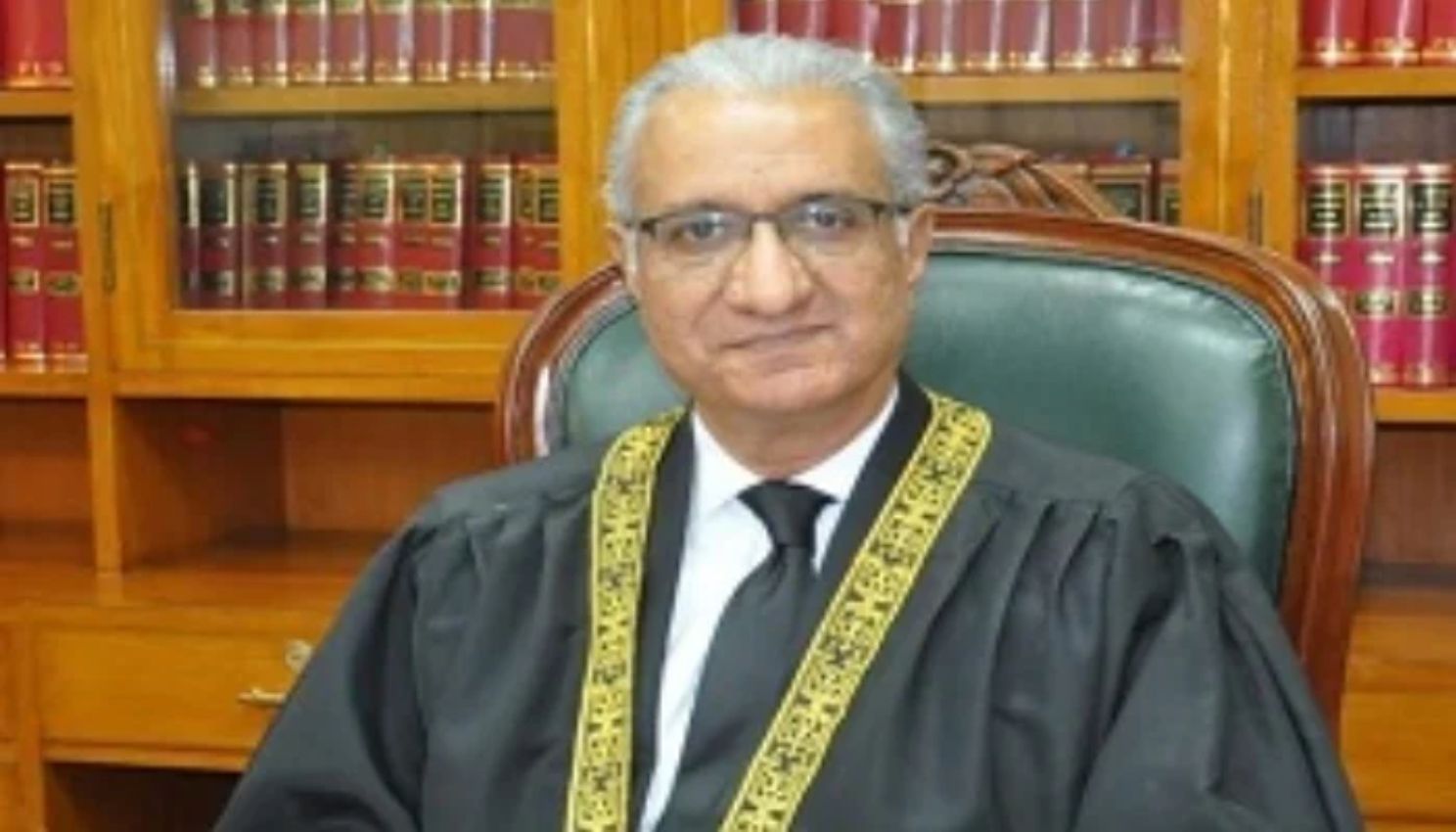

ISLAMABAD: President Dr Arif Alvi on Friday accepted the resignation of Justice Ijaz Ul Ahsan, the third senior-most judge of the Supreme Court who stepped down abruptly a day earlier, on Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar’s advice.

Justice Ahsan resigned under Articles 179 and 206 (1) of the Constitution.

Article 179 allows an SC judge to resign sooner than his retirement age. “A Judge of the Supreme Court shall hold office until he attains the age of sixty-five years, unless he sooner resigns or is removed from office in accordance with the Constitution.”

Article 206 (1) reads: “A judge of the Supreme Court or of a high court may resign from his office by writing under his hand addressed to the president.”

After the president approved Ahsan’s resignation, the Ministry of Law and Justice issued a notification regarding it.

As per the notification, the resignation has been approved from January 11.

The third senior-most judge of the apex court had said in his resignation to President Alvi that he wished not to continue as the top court’s judge anymore.

The resignation came only two days after Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi’s stepped down from his office amid misconduct allegations.

The untimely departures of the senior judges have triggered widespread speculation. The president had on Thursday accepted Naqvi’s resignation.

In his resignation to the president, Ahsan said he no longer wished to continue as the top court’s judge, therefore, he was resigning under Article 206(1) of the Constitution with immediate effect.

Both the judges were considered ‘close’ to former CJP Umar Ata Bandial, with analysts saying that the jurists were involved in issuing controversial orders — along with another judge, Justice Munib Akhtar.

While Bandial was in office, the fault lines between the top court’s judges were visible. This trend diminished when CJP Isa came to the helm, but the damage had already been done.

Senior journalist Hamid Mir told Geo News that two references were being drafted against Ahsan, of which he might have caught wind, leading him to adopt “a way out” i.e. skip accountability.

“This wasn’t unexpected; lawyers were already talking about it. Had he remained in office, he would be facing two separate references,” Mir, a seasoned journalist, added.

“This is a good thing. There is nothing concerning about it. A new tradition has begun: the Supreme Court judges who misused their offices are facing references filed by lawyers,” Mir also said.

‘Controversial jurisprudence’

Born in 1960, Ahsan began his legal career in the 1980s. He was confirmed as a judge of the Lahore High Court on May 11, 2009, and became the LHC’s CJ on November 6, 2015.

He was elevated to the Supreme Court on June 28, 2016, less than a year after serving as the LHC’s top judge.

It is important to note that he was part of the infamous Panama Papers bench that disqualified Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) supremo Nawaz Sharif.

He was also appointed to oversee proceedings of the references that the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) has been asked to file — by the top court — against Nawaz, his family members, and former finance minister Ishaq Dar.

Also, in 2018, Ahsan was part of the five-member bench that had ruled that disqualification under Article 62(1)(f) was “permanent”. Then, he was also part of the bench that ruled that if a person is disqualified, then they cannot even head a political party.

When the matter of no-confidence against former prime minister Imran Khan was in the running, a petition was filed for the interpretation of Article 63-A — whether the votes of party lines will be counted or not. He was part of that bench as well, which ruled that voting against party lines would not be counted, benefiting the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).

Last year, during the Pakistan Democratic Movement’s (PDM) government, the Supreme Court would intervene when the parliament would pass laws. In majority of those benches, Ahsan was included.

In terms of NAB laws, Ahsan had struck them down.

“His jurisprudence has always remained controversial. He has not passed orders that are worth praising,” legal expert Reema Omer said.